Death By 1000 Cuts: John Woo's Hard Target (1993)

- Simon Abrams

- Jan 21, 2021

- 9 min read

Updated: Jan 12, 2022

Cult films with troubled productions or well-known histories of studio interference often present a Rubicon of taste that only diehard fans (especially horror boosters) are anxious to score. You know exactly who you are and where you stand if your love for Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977), Halloween 6: The Curse of Michael Myers (1995), or The Stuff (1985) elevates those compromised, but sometimes brilliant, curate’s eggs to unattainable heights.

And why not? Those movies are better than Balzac’s enchanted cigarettes since they at least exist, albeit in some altered state. And in time, new screenings and home video releases of previously censored or otherwise mangled films like God Told Me To (1976, the “Demon” cut, still tangled up in music rights issues), Inferno (1980), and The Wicker Man (1973) have confirmed what cultists already believed in their hearts: there’s something here, and it’s the stuff that auteurists dream of.

John Woo devotees know this feeling all too well since a few of his post-“heroic bloodshed” pictures either used to or still exist in multiple edits, like the fabled assembly cut of Mission: Impossible II (2000, supposedly an hour longer than the theatrical release), the director’s cut of Bullet in the Head (1990, 25 extra minutes), or the two-part, 4.5-hour version of Red Cliff (2008, don’t even get me started on the 2.5-hour cut).

You can at least see Red Cliff in its entirety on DVD and Blu-ray, just like you can find legal, gray market, or extra-legal copies of stuff like: Woo’s relatively underwhelming two-part historic drama The Crossing (2014, never distributed in the US); the 2.5-hour cut of Windtalkers (2002, about 20 minutes longer than the theatrical release). Even several of Woo’s pre-Hollywood films were tinkered with: during both his Taiwanese Cinema City exile as well as his tenure at Shaw Brothers, first as an apprentice to action filmmaking legend Cheh Chang, and then as a director of solid martial arts programmers and lightly likable comedies (for some additional context and pointers, go here). The only catch is that you already have to know what you’re looking for, and where to look for it.

Hard Target (1993) is another Schrödinger’s Cat of a film that, like Mission: Impossible II, may only exist in a longer, more cohesive form in the minds of Woo’s fans. A longer version of this Jean-Claude Van Damme star vehicle, a New-Orleans-set riff on The Most Dangerous Game, definitely exists (check out William S. Wilson’s detailed Video Junkie breakdown of a 20-minutes-longer cut). Still: Hard Target remains an object of fanboyish speculation given not only the superheroic expectations that were, at the time, put upon Woo — by expectant enthusiasts, critics, industry speculators, and oh yeah, Universal Pictures executives — but also given the picture's production and release difficulties.

There was no real precedent for Hard Target given that it was a negative pickup for Universal, “a relatively bold move on the part of a studio which has never done action movies before,” as Sight and & Sound’s Berenice Reynaud wrote at the time. Manwhile, The Atlantic’s Henry Sheehan called Hard Target “a potential bridgehead for the exodus of Hong Kong movie talent” ahead of Hong Kong’s 1997 handover, while Esquire’s Nathaniel Wice speculated that “if Woo's style survives the relocation, Hard Target could be Van Damme's breakthrough to true mass appeal.”

In 1993, Woo was a “hot director”, as Rolling Stone’s Jeff Giles and Michael Rubiner announced three months prior to Hard Target’s release. Then again, Woo’s pre-Hollywood successes also made him a “cult” sensation in America. Giles and Rubiner even describe him as such later in the same article, quoting Van Damme, who insists that he “pushed for [Woo] like an animal, because I knew this guy was going to be like my James Cameron when Arnold did his first Terminator (1984)." It’s true, Van Damme did fly out to Hong Kong to meet Woo, along with Hard Target screenwriter Chuck Pfarrer. Van Damme also undercut Woo’s vision by attempting to re-jigger the film behind Woo’s back with the help of Universal’s head editor.

Hard Target was a box office success despite seven different mediations with the MPAA (all for the sake of avoiding an NC-17 rating) and a general lack of trust from Universal. Executive Producer Sam Raimi shadowed Woo, and was told to “step in and take over if the director faltered,” as The Hollywood Reporter’s Peter Kelly reported earlier this year. According to Woo, Raimi often stood up for him, but there was only so much that could be done given that Woo didn’t have final cut. Back in '93, Raimi’s quoted in Time Magazine with the only good advice he had to offer Woo: “one day it would all be over.”

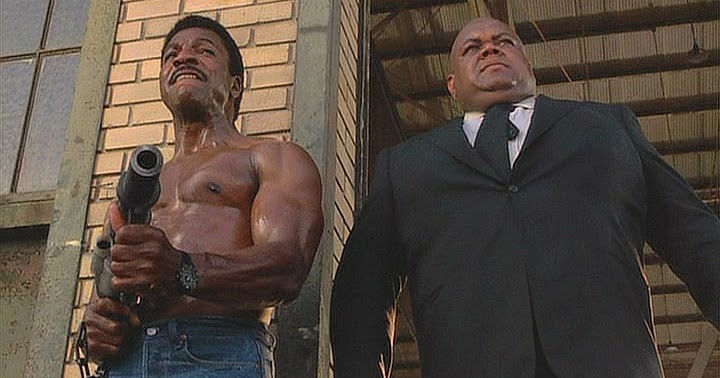

That sort of bleak pragmatism is hilariously antithetical to Hard Target’s giddy and unabashedly garish style. It’s also a funny coincidence given that the movie begins with a ragged foot chase that only ends after Lance Henriksen, as hot-for-murder merc Emil Fouchon, suggests, “It’s like a drug, isn’t it? To bring a man down.” Fouchon and his guys, including right-hand heavy Pik van Cleaf (Arnold Vosloo), like bringing down men who are barely surviving on society’s margins, especially ex-military men since they provide the hardest of human targets. This is presumably why we first meet our hero, ex-marine Chance Boudreaux (Van Damme), counting his change at the Half-Moon Utility Restaurant, a quaint greasy spoon with hand-written over-the-counter signs for pork chops ($4.35), onion rings ($1.55), and a two-egg breakfast ($2.50).

The Half-Moon is an all-American fantasy, a wondrous way station where an unhappy-looking Belgian with a mullet and a trench-coat can awkwardly trade banter with a gumbo-slinging counter-lady (Barbara Tasker). Van Damme’s eyes look up expectantly, though it's hard to say at whom, since we only get a glancing shot of Tasker before she asks Boundreaux about his food. He replies, but only after we get a generous close-up of his pierced ear (a gold ring), then a luxurious close-up of his lips: "A tragedy. The coffee was tolerable, though." These words don't sit well on those lips despite ameliorating rewrites by Pfarrer, but the sheer duration of that close-up speaks to Woo’s considerable faith in Van Damme, both as a performer and his movie’s star. Van Damme may have spent a lot of his time on-set away from his fellow cast-mates — Reynaud describes him as “charming, but aloof” and says that he “lunches alone in his trailer, on a special body-builder's diet”— but on-screen, he appears as iconic and overstuffed as a parade float.

Boudreaux isn’t much of a character, as several of Hard Target’s then-contemporary critics noted: “the roles are little more than job descriptions” wrote Richard Corliss and Jeffrey Ressner in a Time Magazine article entitled “John Woo: The Last Action Hero”, before continuing, “martial artist Van Damme gets to punch out a rattlesnake and follow this moral code: I shoot you three times, then I kick-box your ugly face.” Sight & Sound’s Verina Glaessner also preferred Henriksen and Vosloo’s antagonists to Boudreaux since the movie’s villains are “bearers of self-doubt and vulnerability, marginalized by the script, but at once more interesting themselves and in their relationship to each other than the protagonist.”

These critical assessments aren’t inaccurate, but they are sort of besides the point when applied to an action movie that sometimes mocks its own generic cartoonishness, like when Boudreaux opens his trench-coat in slow-motion to reveal the lethal weapon he’ll use to disarm a group of denim-clad street toughs: his right leg. Boudreaux’s an old-fashioned gunfighter in a world that can’t accommodate that sort of chivalrous outsider. He arms himself with his considerable machismo, a character-defining quality that’s established through Woo’s effects-driven action choreography and extreme close-ups.

No wonder there’s not much to supporting characters played by Kasi Lemmons and Yancy Butler, who respectively co-star as sympathetic but overworked Detective Marie Mitchell and google-eyed romantic interest Natasha Binder. Women tend to be afterthoughts in Woo’s movies since they are usually the object of their male heroes’ thwarted ambition. Women are too pure for Woo’s male-dominated worlds, as Maitland McDonagh, one of Woo’s most rigorous critics, wrote in a 1993 issue of Film Comment. McDonagh notes that “Woo's plots[…]regularly verge on Boy's Own Adventure territory” and complained particularly about the “jarring tonal transitions” in Woo's Hong Kong movies, singling Blind Jennie (Sally Yeh) in The Killer (1989) and Kit’s “clumsy” girlfriend (Emily Chu) in A Better Tomorrow (1986) for their awkwardly comedic featuring.

McDonagh got so much right, and in such vivid detail in her original 1993 piece — her supplementary interview with Woo is also enlightening — that it’s hard to ignore her dismissal of Woo’s champions for what she calls “contemporary Orientalism incarnate.” She understandably stresses Woo’s acknowledged stylistic debt to Western auteurs like Sam Peckinpah and Martin Scorsese, which makes sense given that both filmmakers’ influence is apparent, from Woo’s lithe camera movements, iconic use of slow-motion photography, and half-romantic, half-fatalistic point-of-view. But McDonagh’s side-swipe at what she identifies as Western fans’ uncritical acceptance of the “jarring tonal inconsistencies” in Woo’s films is as telling as her description of Hard Target as “single-mindedly humorless.”

McDonagh rejected the notion that Western viewers "are shut out of some foreign aesthetic that just doesn't play by the rules to which Hollywood has accustomed us”, an apologetic defense she sees as “an appeal to exoticism that risks being condescending.” Admittedly, the fanboyish zeal of some of Woo’s defenders was and still is unbearable, but there are welcome exceptions to that general rule, like former such as Outlaw Vern, who, in his 2016 appraisal, also emphasized Van Damme’s holster-less gam. Vern also doesn’t seem too bothered by Hard Target’s seemingly random New Orleans setting, noting that Pfarrer’s script was rewritten for NOLA in order to better explain Van Damme’s accent. Vern’s not wrong, but neither is McDonagh, who generally observed that the actors in Woo’s films “often seem to have entirely different ideas about tone and emphasis.”

Vern’s piece concludes with praise for Wilford Brimley’s enthusiastically goony performance as Uncle Douvee, Boudreaux’s folksy, horse-riding bayou bootlegger uncle. According to Vern, Hard Target is “one of the few movies where Wilford Brimley, with a bow and arrow, rides a horse in slow motion away from an explosion. That’s usually how I try to sell it to people.” A compelling summation, though the clumsy comedy McDonagh normally attributes to Woo's women is present in Chance's whiskey-swilling surrogate swamp papa. Even Woo admitted (during his 2018 conversation with Peter Kelly) that Brimley’s ramshackle supporting character “lights up the whole film and makes the movie look so much different.”

Barbara Scharres' American Cinematographer feature is the best entry point into Hard Target, being not only the most detailed account of the movie’s production, but also the most thoughtful consideration of Woo’s motives for going Hollywood: “I want to say whatever I want to say and do whatever I want to do with my films[…]I don't want to serve a government I don't believe in.” Woo also enthusiastically describes Hard Target as a “great step forward” in his career, both in terms of the “professional” crew members and advanced technology that it allowed him to work with. His optimism is tempered by direct quotes and paraphrases from frequent collaborator Terence Chang, who recalls being shaken down by triad gangsters throughout the production of Hard Boiled (1992) just one year before Hard Target. Chang also suggests that the Tiananmen Square massacre made leaving Hong Kong something of a priority for Woo, “because it reminded people that 1997 could bring something like that or worse.”

All that said, it's still tough not to wonder what Hard Target would have been like if Woo wasn’t saddled with a litany of unreasonable expectations. It sure would be nice to see Universal release Woo’s preferred longer cut (the low-quality 126-minute edit that's been floating around the Internet for years), though that wouldn’t magically improve the movie’s less-than-ideal production. You can tell that even Woo’s most outspoken and well-spoken contemporary defenders were and still are at a bit of a loss when it comes to explaining his brilliance given the evidence of Hard Target’s lumpy theatrical cut. Even Scharres’ piece over-stresses the intricate camerawork that contributes to the movie’s brilliant concluding set piece, as well as the undaunted and hard-won respect that Woo’s crew had for his “professionalism.”

Woo would soon work on superior Hollywood action programmers (such as the gonzo Cage/Travolta showdown, Face/Off [1997]), while a few Hong Kong directors followed him to America*. There’s even a fun decades-later DTV Hard Target sequel starring Scott Adkins, directed by Dutch filmmaker Roel Reiné, which, like the cult movie version of a decent cover song, mostly reminds fans of everything we love about Woo’s original movie.

But what could Woo have done with Hard Target if Pfarrer’s script was stronger, Van Damme’s performance were looser, and Bob Murawski’s scene-to-scene editing wasn’t so unusually patchy? I tend to agree with Variety’s Emmanuel Levy, who wrote that the theatrical cut is a “compromised work” that’s “hampered by a B-script with flat, standard characters, and subjected to repeated editing of the violent sequences to win an R rating.” I also love Hard Target’s stylistic peculiarities about as much as its explosive, sizzle-reel-ready highlights. I mean, who could say no to Lance Henriksen banging away at Beethoven’s “Apassionata” with the look of a man possessed, despite an otherwise alarming lack of contextualizing character development?

Speaking of Henriksen: he spoke with Film Comment’s Gavin Smith in 1993 about adding some backstory to his character, if only for himself. He describes Fouchon as “an ex-French Foreign Legion guy who was fighting in Angola and Mozambique as a mercenary”, and adds that that “background starts spreading out into everything else. Suddenly you don't have to act arrogance or ignorance — I've got something I'm really doing.” The resulting “absolute control” that Henriksen brings to his character translates well on-screen, as McDonagh noted when she praised his “pulpishly perfect” performance. Still, I can’t help but wonder what a movie worthy of Henriksen’s intensity, let alone Woo’s ingenuity, might have looked like. Hard Target will probably always be a for-fan’s-only proposition, but if you already like Woo’s movies because of his style, you probably already know the good stuff when you see it.

*Van Damme told me that he’s especially proud of his Ringo Lam movies, but both of his Hark Tsui collaborations are more impressive.

Simon Abrams is a film critic whose work has appeared in various publications, including Ebert Voices, The New York Times, Vanity Fair, and Vulture. He is also the co-author of "Guillermo del Toro's The Devil's Backbone" with Matt Zoller Seitz.

Comments