His Own Worst Nemesis: The Films of Albert Pyun

- Brandon Streussnig

- May 20, 2022

- 8 min read

For most of my life, Albert Pyun was a punchline.

Simply through cultural osmosis - be it bad YouTube channels, MST3K, or someone’s janky blog - Pyun became the bozo responsible for a deluge of sub-sub-schlock, with the "highlight" being his disastrous 21st Century adaptation of Captain America (1990). It wasn’t difficult to give into the impulse to relegate Pyun and his body of work to the mental waste bin of “great VHS cover, awful movie.”

Still, the problem with this line of thinking is that you’ll never know anything about Albert Pyun unless you experience his filmography for yourself. Being proven wrong is a hell of a feeling, and Pyun’s legacy is far more important than being labeled the output of "the modern Ed Wood." Sitting down with a Pyun joint exposes you to many joys: muscular women, musical numbers, gorgeous matte paintings, robots, often all at once. Most importantly though, sitting with a Pyun is unlike anything you’ll ever experience. It’s like entering the mind of a true creative madman who possesses an impossible to contain imagination. Beyond schlock, beyond “B-movie”, beyond mere definitions of "good" and "bad", there’s the hazy, unabashedly earnest dreamworlds of Albert Pyun.

Pyun’s career started with a claymore strike to Hollywood’s face in the form of the high fantasy rip off epic, The Sword and the Sorcerer (1982). Modestly budgeted, absent anything resembling star power, Pyun’s own sorcery was still well on display. In what would become a running theme throughout his work, he had an unmatched ability to spin gold from pennies. On a paltry $4 million budget (and working against a meddling junkyard producer), Pyun weaves an epic web of adventure full of dingy medieval dining halls, gaudy royal garb and demonic effects. It’s silly, but Pyun’s brand of silliness is rarely cringe inducing. His love for dorky heroics and men of might is so pure that a wooden one liner croaking out of Lee Horsely’s mouth hits your ear as naturally as Bruce Willis grunting “yippie-ki-yay, motherfucker.”

It’s all of a piece, Pyun’s earnestness an infectious delight. More than that, Pyun’s craft is astonishing from film one. His eye for action is almost unparalleled, and no one lights like him. There’s no reason for The Sword and the Sorcerer to own splashes of red and magenta that would make Argento yelp, yet Pyun can’t help himself. It’s gorgeous stuff, immersing you deep into this airbrushed realm he’s conjured from thin air. Feeling right at home alongside Conan The Barbarian (1982), The Sword and the Sorcerer became an unlikely $40 million hit. You’d think that kind of success would have studios throwing money his way for years to come, and for a time that was actually true. Pyun was attached to all manner of films - most famously a take on Total Recall written by Ronald Shusett and starring William Hurt - but, for one reason or another, nothing really materialized that would skyrocket him into the next stratosphere of creative stardom.

Instead, Albert was left to eternally work with studios breathing down his neck, and budgets that amounted to little more than $10 and a ham sandwich. Pyun's most iconic radioactive dreams - movies like Cyborg (1989) or Nemesis (1992) - often centered around cyberpunk futures and robotic menace of all stripes. Over the years, he’s stated that these things don’t really interest him, but shooting in dilapidated locations were usually the easiest on his increasingly tight budgets. Pyun was constantly forced to cram his own passions and ideology into his pictures, and this smuggling is what makes his work so special. An admitted lover of rock operas, there’s a refreshingly hopeful authorial voice behind the camera. In the hands of an anonymous gun-for-hire craftsman, something like Nemesis is a forgettable piece of Terminator-lite schlock. In Pyun’s hands, you’re thrust into a dreamy future shock of oddballs and freaks, backs against the wall and better days fleeing their faces.

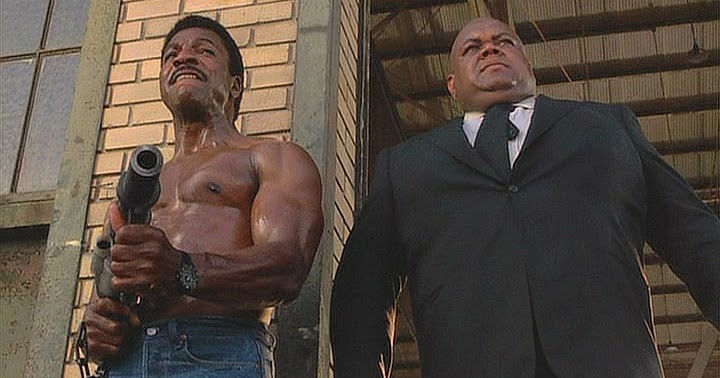

Patiently paced, Pyun’s eternal optimism bleeds through like a balm against the typically macho predilections of the genre. Olivier Gruner’s ex-cop, half-cyborg Alex floats through dusty streets, steely eyes gazing at the world around him, a jaded soul who can’t help but do the right thing. Surrounding Alex are impossibly muscular women, dominating his every move and staple of a certain budget, Tim Thomerson hot on his trail. With Gruner basking in all the oranges and tans of the wasteland around him, Pyun lets you marinate in this apocalypse and, even when none of it really makes a lick of sense, it’s real. You just feel it. It’s a perpetual magic trick. These things are cheap and often can't shake that inherent lack of resources but, through sheer force of will, his imagination overrides yours and tears down any cynical inhibitors.

On top of all that, Pyun's eye for action is out of this world. Nemesis begins with a gun ballet that rivals almost anything John Woo put to film. From there, Pyun peppers Nemesis with some truly wild stunts. From Gruner escaping a couple of goons by literally shooting a Looney Tunes-esque hole in the floor of his hotel and falling through multiple stories, to a fist fight down a mudslide culminating in a robot’s head being beaten apart, Pyun pulls world class VFX out of thin air. Despite all his idiosyncrasies (or, perhaps, because of them), Pyun doesn’t get the credit he deserves in this department. Whether it’s casting Gary Daniels early in his career, or essentially giving birth to 87-Eleven via Nemesis 2: Nebula (1995), as Chad Stahelski’s rubber suited monster does a terrifying free off a building, Pyun’s admiration for the craft of stunt-work and those who perform it is utterly remarkable.

As the Nemesis series trudges along, it becomes a much more bizarre, yet no less singular, franchise. Relegated to the forgotten plastic piles of VHS history, these shelf-stuffers become an intoxicating mix of action, art house, and softcore. Swapping out Gruner for bodybuilder Sue Price as Alex, Pyun uses the sequels to explore his own desires and dreams. Nemesis 2 essentially plays like lo-fi Mad Max (1979) as Sue Price, in little more than a loincloth, races across the desert on foot. Nemesis 3: Time Lapse (1996) is possibly the least effective of the bunch, as it’s a redux of Sue’s attempted escape from her fascistic pursuers, allowing unused footage from 2 bear the brunt of the narrative.

Nemesis 4: Cry of Angels (1998) is where things get truly mystifying, as we’re thrown into the far future with a fetishistically ripped Sue Price hunting people down, often naked and post-sex, through Eastern European back alleys. The narrative strands are borderline irrelevant, but Pyun’s hope for a better tomorrow is the primary vibe, and if you’re willing to catch it, these are daydreams well worth falling into. If one were to go Full Galaxy Brain with these junky sequels, you might even subscribe to the idea that Pyun is using Price’s Alex as a stand-in for himself: a strong-willed being forever trying to outrun the overseers who refuse to understand their vision. Or maybe Pyun just likes yoked women crushing impotent men? Who’s to say, really?

Pyun’s no budget opuses are the films where he truly gets to be himself, away from all the robotic nightmares of tomorrow. In joyous sci-fi yarns like Radioactive Dreams (1985) and Vicious Lips (1986), he gets to bring his love of rock opera to the fore. In the former, it’s an unmitigated success as two Marlowe-obsessed brothers leave their bunker and dance their way across the wastelands, changing the hearts and minds of many mutants they cross dusty paths with. The latter’s a bit shakier, sometimes the lack of budget ends up being too much for Pyun to overcome and we’re stuck in an aimless one set dirge. Entwining the two is an overwhelming optimism and love for music. Both feature extended performance set pieces, often letting an entire song play out. It’s obvious this is where Albert’s happiest, and although he eventually made an unofficial sequel to Walter Hill’s Streets of Fire (1984) - the oddly titled Road to Hell (2012) - it’s a shame he never got the resources of his rock 'n roll idol.

It’s in the third part of an unofficial trilogy with Dreams and Lips where Pyun made his masterpiece. It’s also possibly his most derided film. Alien From LA (1988) is best known for being featured on an episode of MST3K and has been widely been mocked ever since. Let’s not kid ourselves, the Kathy Ireland-fronted adventure, mixing equal parts Jules Verne and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, is undeniably silly. From the bizarre choice Ireland makes to speak in high-pitched baby voice, to Pyun’s unmitigated sincerity, you can’t really fault people for not picking up what he was laying down. Viewed three decades later though? It’s an unqualified triumph of imaginative genre filmmaking.

After laying a bit of perfunctory groundwork, where a Valley Girl goes searching for her missing father in Africa (no, really), Pyun drops you into an underground world wholly unlike anything ever put to film. The sects of various people, their cadence of speaking, the rules of the world itself, there’s an entire history bursting out of every seam. The confidence in which Pyun flexes his imagination over a very short 87 minutes isn’t an accident. Being given some of that Golan and Globus cash was clearly a godsend, because he stretches it to the moon and back. His sets are breathtakingly inventive, more so than most adventure films at the time (looking at you Goonies [1985]), his costumes well worn and considered and as always, and matte paintings that’ll make your eyes pop out of your head. Above all, it’s his earnestness that wins you over, because Alien From LA is a damn delight. Wearing its heart firmly on its sleeve, it’s something of a rarity now: wholly uncynical piece of pulpy adventure, literal dreams made manifest.

When you go in for a Pyun, the results can range from "hidden gem" to "please, keep that hidden forever", but nine times out of ten, the former tends to win out. Trekking through his filmography is a verifiable buffet of the wildest shit you’ll ever come across, sporting a level of craft and wonderfully dorky sincerity that you can’t believe exists. You also start to get a little angry. How could the system have failed an imagination this vast? How could it deny a filmmaker consistently doing the impossible? Forget the effects and stunts he pulled off, this is the guy who pulled legitimate chemistry out of Andrew Dice Clay and Teri Hatcher in his excellent Big Trouble in Little China (1986) riff Brain Smasher...A Love Story (1993).

Further complicating his legacy is the impossibility of finding the majority of his work, at least legally and legibly. Sure you’ll find bad rips on YouTube or bootlegs at conventions, but it’s inexcusable that some of the most stunning genre work of the '80s and '90s is essentially lost to time. Thankfully, boutique labels like Shout, MVD, and Vinegar Syndrome are slowly fixing that. One hopes that, in the years to come and as more of his work is restored, Pyun’s reputation will only continue to be repaired. He certainly deserves to see it happen on a much wider scale while he’s still here. Simply put, Albert Pyun is one of the most gifted imagemakers we’ve ever had, budget be damned. When his contemporaries were being given the keys to the kingdom at massive studios, he was out there in the trenches cooking up futureworlds, hidden cities and grand musical numbers. He was a dreamer in an industry of cynics whose mind couldn’t be contained by wallets and mandates. A true soldier of cinema from another place, another time.

Brandon Streussnig is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in The Playlist, Fangoria, and Film Combat Syndicate.

Pyun is garbage.