Ryder On the Rain: The Hitcher (And Robert Harmon's Other Road Horror)

- Jacob Knight

- Nov 2, 2021

- 9 min read

Updated: Jan 12, 2022

We’re in a police station. Even the cops aren’t happy to be here. Behind a podium, the Watch Commander (James Luisi) calls roll while his subordinate boys in blue grumble amongst themselves. Upon reaching Donnelly’s name on the list, there is no response. A fellow officer glances back at the seat where the veteran LA motorcycle cop usually enjoys his morning cup. It’s empty, just like it is every year before it on this date. Because this is when Donnelly (consummate heel, Charles Napier) takes his annual vacation in the desert to work out his various grievances with his fellow man.

Superficially, China Lake (‘83) feels like Robert Harmon’s dry run for a script he hadn’t even read yet. A dusty, sparse thirty-four minute serial killer character study that offers less motive for its central figure’s heinous crimes than Jim Thompson assigned to The Killer Inside Me's savage West Texas deputy, Lou Ford, Harmon wrote, directed and shot the short to act as an artistic calling card after graduating from set photography gigs on low budget genre fare like Tourist Trap (1979), Fade to Black (1980) and Hell Night (1981). By the short’s chilly, morally vacuous conclusion, we’ve witnessed two horrible killings before the cop returns to his roll call seat, possibly still smiling to himself regarding how good it’d feel to cook a rude construction worker (character actor royalty, Bill Sanderson) on a diner’s red hot grill.

By all accounts, Harmon’s feature debut The Hitcher (1987) probably shouldn’t even exist. Despite Eric Red’s overlong, idiosyncratic horror script - which (in a possible moment of apocryphal “print the legend” tomfoolery) may have been inspired by a creepy chance encounter the scribe had with a real life hitchhiker during his drive from New York to Austin, Texas - becoming a disreputable sensation around Hollywood, most producers still believed the story was too mean-spirited for the mainstream. In her superlative analysis of The Hitcher for Arrow Films, genre scholar Alexandra Heller-Nicholas even relays a story where legendary cult cinema enabler Jim Jacks (Raising Arizona [1987]) labeled the project “ruining trash” for Harmon’s nascent career behind the camera.

Based on that statement alone, it’s arguable Jacks had never laid eyes upon China Lake, and not just because it was the filmic instrument that helped recruit both Rutger Hauer and C. Thomas Howell to star as hunter and prey for The Hitcher. No, anybody who saw China Lake didn’t just know that Harmon would be the right guy to help bring Red’s mythic, desolate tale of desert savagery to life, but that he’d do so prophetic verve. Because on Harmon’s visions of America’s highways, we are all alone, frustrated, and looking to work out nigh overwhelming sexual anxiety on whatever poor fellow is standing by the blacktop with his thumb out. These hills don’t have eyes. Instead, they’re blind to sin and excessive cruelty; no more witnesses than an uncaring anti-Savior keeping watch in the rumbling storm clouds.

Though road horror had been in Harmon’s blood for the better part of the ‘80s, it was an Australian who became The Hitcher’s chief co-architect, at least in terms of the arid envisioning of a single two-lane desert route becoming a Hell from which young Jim Halsey (Howell) cannot escape. John Seale was already a legend in Oz, having paid his dues as a camera operator on everything from Philippe Mora’s outlandish Dennis Hopper Outback Western Mad Dog Morgan (1976) to Peter Weir’s ethereally apocalyptic art film The Last Wave (1977). This was before graduating to cinematographer on David Hemmings’ supernatural plane crash opus The Survivor (1981), as well as Weir’s American Oscar darling, Witness (1985). So, if you’re keeping score at home, Seale was nominated for a Best Cinematography Academy Award the year before The Hitcher - a movie most believed shouldn’t be made at all - was released.

Seale’s presence no doubt accounts for why The Hitcher resembles a Death Valley cousin to the Ozploitation movement that overtook Australian cinema during the ‘70s. Just as Seale and his artistic brethren transformed the Outback into a stark void seemingly without borders, Harmon and his cinematographer work overtime to remind us that there are still sections of so-called “civilized nations” which were never pioneered (because they never could be). Once rain starts pounding the drive-through metal box Halsey is piloting from Chicago to Los Angeles, the suffocating heat of China Lake gives way to a black torrent where young Jim's car is now a coffin, set to be drowned in elemental quicksand. Nothing about this world is forgiving, and the way Seale’s camera transforms from claustrophobic to panoramic (and back again) is no small miracle.

Some complain that they don’t buy The Hitcher’s central premise. In fairness, why would a seemingly well-adjusted kid from the Heartland pick up this ragged, blue-eyed stranger (Hauer) from the side of the road? By the time the ‘80s rolled around, enough disillusionment had occurred in the United States to make any sane person double guess Jim’s altruistic actions. From national crises like Vietnam and Watergate, to the birth of serial murderers such as Ted Bundy or David Berkowitz, the nation’s psyche had become distrustful of anything that could invade their ostensibly safe spaces (our living rooms and cars being prime examples). However, given Halsey's increasing sleepiness, we have to assume that a little bit of fear and loneliness went into him opening the passenger door and uttering, “my mother told me to never do this”. Because, after all, only dogs desire to die alone.

Howell has confessed in the past to being intimidated by Hauer on set, and that visceral anxiety comes through in the manic fashion in which Halsey attempts to process his newfound adversary’s whispered threats of bodily dismemberment and (eventual) death. When Ryder confesses to cutting the arms, legs and head off of a fellow traveler - whose VW beetle passed a sleeping Jim in the wee hours of this now endless night (or is it morning?) - we certainly believe him. Flanked by windows washed in waves of aggravated precipitation, Rutger’s icy eyes shine in the shadowy interior of this practical sedan. We don’t know anything about his John Ryder and, as far as we know, he might be a demon, sent from the bowels of Hades to slaughter all he encounters.

There have been a few interpretations tossed out during the three decades following The Hitcher’s release, box office floundering, and eventual cult resurrection via home video and numerous late night HBO airings. The most prominent is a queer reading between John and Jim, what with all the crotch threats and lurid, sweaty electricity that passes between the two passengers and almost keeps this drifting, waterlogged sarcophagus afloat all by itself. This interpretation isn’t without merit, as Hauer taps into the fluid sexuality that made his work with Dutch provocateur Paul Verhoeven (Robocop [1987[) so memorable. Unrelated (though, perhaps, not coincidental), Rutger even played an erotically charged hitchhiker in one of his earliest Vehoeven collaborations: the melancholy rumination on love’s passing, Turkish Delight (1973). Over the years, Red has vehemently denied peppering his script with homoerotic subtext, insisting Hauer summoned it all in the moment which, if true, is as pure an illustration of action overruling intent if there ever was one.

Nevertheless, the monster’s motive doesn’t become clear until well into the movie, after he’s played with his new prey long enough to satisfy whatever sadistic urges burn in his belly. “I want you to kill me,” Ryder whispers to Halsey, and the true nature of The Hitcher is revealed. This isn’t a love story, by any means. Instead, it’s a coming of age tale, in which a psychopath breaks in his new protégé against their will. Jim isn’t a mere toy, but rather a chosen heir to Ryder’s nigh supernatural evil. With this bullied metamorphosis comes a series of escalating set pieces, wherein Ryder pushes his former driver up against both man and machine, leading to showdowns with Texas Rangers and the dismemberment of the one girl who could’ve possibly saved Jim’s soul.

The introduction (and eventual destruction) of Nash (Jennifer Jason Leigh) only strengthens the homoerotic subtext that bubbles in this beast’s engine. Leigh, easily one of the greatest (yet still undervalued) actors of her generation, has spent the entirety of her career seeking out idiosyncratic material. Just the year before The Hitcher released, Stacy Hamilton from Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982) was raging along with Paul Vehoeven (not to mention Hauer) in the madman auteur’s Crusades horror show Flesh + Blood (1985). Over the next decade (and into the early ‘90s), she’d traverse the surreal, Lynchian hallways of a possibly haunted nightclub in Heart of Midnight (1988) and go deep cover in the Eric Clapton scored heroin buster, Rush (1991). Leigh's entire career is peppered with fascinating oddities, in which she plays a pivotal, transfixing role in each and every one.

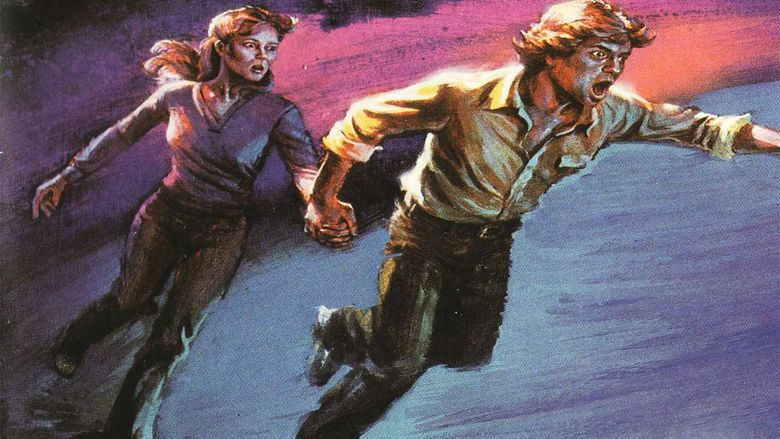

As the surprise Bonnie to Jim’s fear the reaper Clyde, Nash goes from unwilling accomplice to savior, before being torn to pieces between a pair of semis. Her death is easily the most shocking scene in a movie filled with filthy grotesqueness (though, in a feat of editorial restraint, we technically never see frame one of her actual splitting). The fact that we came to love Nash as quickly as we did is practically all Leigh’s doing, as she morphs her trademark tranquil sexiness into tough girl attitude, freeing Halsey from the clutches of determined lawmen. Despite Red’s script never really giving the girl defined reasoning for her aid, we still totally believe this truck stop waitress would pick up a gun and hop in for what would ultimately become her joyride into oblivion. Because Leigh wills Nash into being - a fully formed girl next door who owns more guts than either of these dusty dudes...and ends up paying the price for them.

Yet another interpretation some have bandied about over the years isn't supported by the film's text at all, and that’s the theory that John Ryder and Jim Halsey are, in fact, the same guy. Granted, Ryder often inexplicably teleports into scenes, giving this relentless pursuer an almost ghost-like aura. And, in fairness, this reading acknowledges the movie's main theme: Ryder’s need to transform the innocent Halsey into a killer, thus destroying the “aw shucks” All-American boy who has nothing but the future ahead of him. It's a vision quest with twisted metal and scattered buckshot puncturing any policeman who dares interfere with the primal ritual. So, while the theory that they’re two psyches in one mixed up mind doesn’t hold up visually (the mechanics of Nash’s death alone wouldn’t make sense) it’s still a somewhat healthy method of unpacking a work that’s superficially nothing more than a thrill-a-minute action riff.

“The car crash is a fertilizing, rather than a destructive, event,” says the sexually ambiguous cult leader, Vaughan (Elias Koteas), at one point during David Cronenberg’s chilly vehicular masterpiece, Crash (1996). The victims in Harmon’s Highwaymen (2004) would probably disagree. A spiritual sequel to The Hitcher, the director returns to the road almost twenty years after Jim Halsey and John Ryder’s final shotgun showdown, which left Hauer’s spectral maniac dead on the blacktop, a veritable fleet of police vehicles demolished, and Howell’s boyhood innocence shredded amongst blood, sand, and broken glass. Only now, we have a new agent of mechanical chaos, Fargo (Colm Feore), picking off anonymous victims one-by-one across the vast expanse of America’s traffic system, leaving their bodies as nothing more than morbidly comforting statistics to be rattled off at the beginning of support group meetings.

Like Vaughan and the rest of the fucking, sucking, suicide kings and queens who inhabit the aforementioned lipstick and chrome JG Ballad adaptation, Harmon’s Highwaymen players are forever (a)roused by the tragic collisions they experience, and not just physically. Rhona Mitra’s Molly - the closest thing we get to a “Final Girl” in this pre-Death Proof (2007) road slasher - not only loses her parents in a childhood accident, but later becomes the lone survivor of Fargo’s reign of terror. Meanwhile, Rennie (Jim Cavieziel) actually witnessed his wife’s murder under the bumper of Fargo’s ‘72 El Dorado, as he mercilessly swerved to crush her fragile feminine form. Now, the widower is a wayward rogue, kidnapping Molly following her own tragic tunnel incident, during his seemingly never-ending crusade for justice behind the wheel of a souped up ‘68 Plymouth Barracuda.

Despite his own transformative backstory - an insurance agent turned serial slayer who was aroused by car crash photos - it’s tough not to view Fargo as the “what if?” extension of the wreckage left at The Hitcher’s grim conclusion. Like, what if Jim Halsey became John Ryder - a violent sociopath who now got off on causing as much pain with his car as humanly possible? And what if Highwaymen was essentially Robert Harmon’s take on a Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter (1984) style blacktop slasher, told through the POV of one victim out to finally conquer his own personal Jason Voorhees once and for all? If anything, it’s another car stunt showcase, scored floating beauty by Mark Isham (the electro pioneer who also provided The Hitcher’s haunting cues), and filmed with an almost fetishistic appetite for destruction*.

When taken as a triptych, China Lake, The Hitcher, and Highwaymen become Harmon’s grand statement on the most banally deadly element of our everyday existence: public roadways. Because every single day, when you get up, get dressed, and head out your door - whether for work or for play - death could be waiting for you once you get behind the wheel. Only your sad demise probably won’t come at the hands of a determined murderer like Officer Donnelly, John Ryder, or Fargo. It’ll just be someone you’ve never met before, who fell asleep at the wheel, drank a little too much, or ran a stoplight because they were late for work. That’s the truly primal fear Harmon’s movies tap into: the fact that a good number of us die alone on the road, and never saw it coming.

*Though John Seale would arguably top every car crash extravaganza when he shot George Miller’s fourth (and arguably best) Mad Max picture, Fury Road (2015).

Comments