The Busted Flush: Darker Than Amber (1970)

- Jacob Knight

- Jan 26, 2021

- 8 min read

Updated: Jan 12, 2022

It takes prolific pulp novelist John D. MacDonald twenty-eight pages into The Deep Blue Good-by (1964) to offer up anything remotely resembling a physical description of Travis McGee - the boozy, brawling knight errant who’d earn himself a best selling dime store series that’d sprawl on for twenty-one entries. Nevertheless, the profile is well worth the wait, as MacDonald weaves just one of many rambling, first person pieces of hard boiled prose into the fabric of this sun bleached noir, coming straight from our main man as he wrestles with the existential notion of sleep aboard his beloved houseboat, The Busted Flush:

"What an astonishment these night thoughts would induce in the carefree companions of blithe Travis McGee, that big brown loose-jointed boat bum, that pale-eyed, wire-haired girl-seeker, that slayer of small savage fish, that beach-walker, gin-drinker, quip-maker, peace-seeker, iconoclast, disbeliever, argufier, that knuckly, scar-tissued reject from a structured society.”

Over the course of nearly two dozen novels, a variation of Travis’ self-indulgent vision of himself would re-appear several times, typically sandwiched between the Floridian salvage operator’s views on everything from New York City (unsurprisingly, not a fan) to poodles (surprisingly, a fan). After all, these are his stories, told with the flair of a barstool Shakespeare who discovered his own brand of saltwater poetry long ago; blue collar iambic pentameter to match the scar tissue that riddles his bronzed body.

Imagine Philip Marlowe, Charles Bukowski, and Hamlet, all rolled up into one muscular package, then add in a splash of deckhand moral code for good measure, and you’re sailing the same turbulent seas as our reluctant hero. Operating as a hyper-masculine fictional avatar for MacDonald, Travis sets off on adventures that the author couldn’t, much in the same way James Bond acted as a stand-in for Ian Fleming. No doubt, MacDonald would refute this comparison, labeling McGee (first named “Dallas” before becoming “Travis”) a “son of bitch” best friend he’d spend several months out of the year with in order for the series to become successful.

In a letter to legendary journalist T. George Harris (who was then working as a senior editor for Look Magazine) dated December 9th, 1963, MacDonald confesses to pounding out over 175,000 words before finding Travis’ perfect balance between being “too intense” and too much of a “smirking jackass”, even going as far as placing Travis in a story where he refused to act, with McGee's “built-in shit detector” going off as the fictional investigator interrogated his own creator’s sanity. Meanwhile, MacDonald rejected aligning himself (and, in turn, McGee) with the heroes of his day, confessing to Harris:

“I could not endure such a close association with that notable gourmet - James Bond. And no sane man would waste five minutes on Mike Hammer or Shell Scott or Perry Mason. Mike Shayne would give me a spastic colon. I think I could get along reasonably well with Lew Archer. Sam Spade was too effing intense. Gideon is too noble and reserved. I can’t remember at the moment the name of Chandler’s guy, but he, like Lew Archer, shares some of McGee’s special viewpoints and reactions.”

Nevertheless, while MacDonald may have resisted his crime fiction peers, he no doubt borrowed the narrative equations that added up to plots of many noir potboilers. From The Deep Blue Good-by on, there was always a woman in danger, who sought out Travis’ peculiar brand of services, usually via reference from one of McGee’s bohemian chums. If there was any money in the mystery to be solved, McGee agreed to salvage whatever these poor lasses were owed for half the treasure, almost always from an abusive man who acted as a dark mirror to Travis' own admittedly antiquated brand of brusque virility.

This undocumented agreement usually led to Travis taking on a companion (again, almost always female) - a relative or close personal/professional relation of the quarry in question - who would often be skeptical of McGee’s methods. Still, the big lug time and again proved himself to be a charming bruiser, often bedding the beautiful new friends and even dating some in the books’ epilogues, after their adventures took this trophy fish out of his usual calm waters aboard his beloved houseboat that he won in a card game a few years back (hence the name).

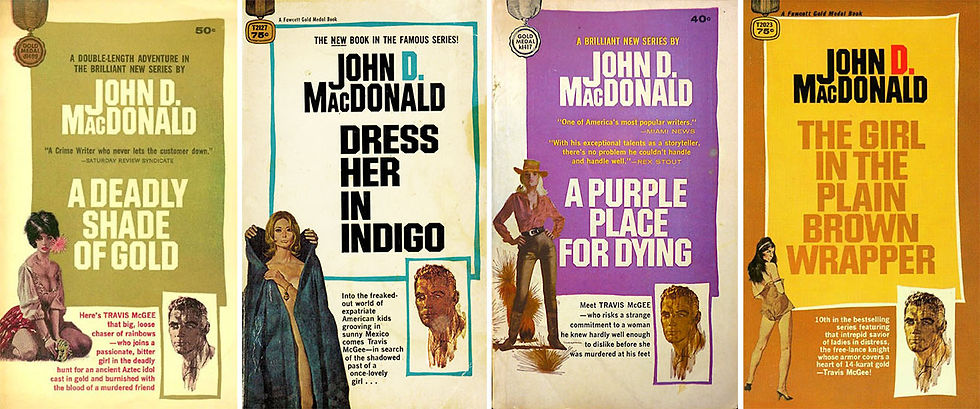

There were jaunts to New York (Nightmare in Pink) and the Arizona desert (A Purple Place For Dying), where psychedelic mental hospitals and corrupt land moguls awaited McGee's arrival. Movie stars sometimes got caught up in lurid blackmail schemes (The Quick Red Fox). Yet Travis always ended up alone at the end of these endeavors, licking age old wounds and admitting that he will always be a rogue, swimming like a shark until he finally stops and dies, another forsaken soul who could never settle down.

Strangely enough, Darker Than Amber (1970) - the first and, to date, only* film adaptation of MacDonald's famous character (featuring Rod Taylor slipping into the bohemian salvage operator’s boat shoes) - is actually based on the seventh novel in the series. Though serials and loose franchises had floated around both cinemas and television, this iteration arrived during the infancy of a filmmaking mode we take for granted fifty years later. For reference, we were only six James Bond films deep when Darker Than Amber hit theaters, with George Lazenby donning the tux for his only outing as 007 the previous year, in Peter Hunt’s once misunderstood (and now rightfully celebrated) psych-action epic, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969).

Yet this dearth of popular precedent didn’t prevent screenwriter Ed Waters, who’d mainly sharpened his pen on small screen pulp like Mannix and Police Story, or future Enter the Dragon (1973) shooter Robert Clouse from making an intimate picture that almost exclusively plays to fans of the novels. There’s no grand introduction to Travis or The Busted Flush. Nor do we receive anything resembling a thorough explanation as to his relationships to trusty moral anchor, Meyer (Theodore Bikel), or floating houseparty madam The Alabama Tigress (Jane Russell). We do get to see him pilot Miss Agness, the vintage Rolls Royce Travis transformed into an all-purpose utility vehicle. In a weird way, Waters and Clouse transmute these elements into disparate stars in a universe readers were already familiar with, and watchers were being trained to look out for in future installments (of which there were none).

This borderline en media res approach to big screen myth-making actually works to help Clouse’s version of Amber capture the spirit of MacDonald’s novels, because the original author was just as disinterested in explaining himself as the movie is. Instead, what we receive is a lo-fi swampy miasma of Floridian noir, peppered with McGee’s trademark masculine philosophical musings (“...a tumble with a willing woman is only worth it if there’s feelings involved…”), a languid old school approach to solving the movie’s central mystery, and a knock down, drag out climactic fight that’s one for the exploitative ages. Though interviews on the subject are scarce, you don’t need the writer or director to tell you they were experts in the sweaty, beer swilling sandbox they were playing in.

Of course, Darker Than Amber revolves around an ill-fated girl: Evangeline “Vangie” Biller-Person (Suzy Kendall, of Bird With the Crystal Plumage [1970] infamy), who’s dumped off a bridge and practically right into a fishing Travis and Meyer’s laps. After retrieving her anchored body from the bottom of the bay, Vangie is nursed back to health and McGee becomes intrigued by her past life prostituting and robbing rich men of their money on cruise ships. But before Travis can uncover just who tossed the pretty girl to certain death, she’s pushed into oncoming traffic, creating a full-scale murder conspiracy that the bronzed knight feels obligated to unravel.

Rod Taylor wasn’t MacDonald’s first choice to play McGee, but that doesn’t stop the square-jawed Australian actor from inhabiting the character so thoroughly that it’s tough to imagine anyone else from that particular period connecting with the material on such an instinctual level. Much how he did in Jack Cardiff’s men on a mission masterwork Dark of the Sun (1968), Taylor possesses a world weariness that soaks in MacDonald’s prose. McGee is a loner; a rogue charmer who doesn’t belong in any sort of structured society, so it makes sense that he takes his retirement “in installments” with each salvage operation.

Nevertheless, Taylor also fully realizes the chameleonesque quality that makes McGee such a reliable underworld operator, his boxy frame and seasoned brown skin still looking good in a seersucker suit. Because while Travis may not belong in bougie shops or aboard fancy yachts, that doesn’t mean he doesn’t know how to act the part. And Taylor seems to be having a ton of fun taking on a role that is as much about the art of adaptation as it is adhering to the beach bum’s nigh inflexible moral code.

If you've watched at a least a decent amount of exploitation movies from the ‘70s and ‘80s, there’s already a solid chance that you’re familiar with the grizzled visage of William Smith. Sounding like he’s spent the majority of his life gargling gravel and owning an intimidating presence not too far removed from a dive bar skull-cracker, Smith haunted various low budget genre films for five decades. Smith’s career arguably peaked in the ‘70s, where he’d appear in multiple films per year (Darker Than Amber is just one of the actor’s six titles from 1970), ranging from rough and tumble biker pictures (Run, Angel, Run! [1969], The Losers [1970]), explo-hybrid curiosities (Grave of the Vampire [1972], Invasion of the Bee Girls [1973]), and Blaxploitation deep cuts (Black Samson, Boss Nigger [both 1974]). In short, if you needed a heavy, hardened detective or horrible racist, Bill Smith was probably your guy.

Bleach blonde, bodybuilding pimp Terry Bartell was both a perfect role for Smith, as well as possibly being the very best villain to pit against Travis McGee for his initial silver screen mystery. Often, the antagonists McGee went up against acted as dark mirrors to his own masculine code; thwarted mutations of his moral compass who ended up distressed and ultimately destroyed their damsels, leaving a wreck Travis had to clean up and punish these hooligans for creating**. Bartell’s navigation of the high seas (via various cruise liners) and exploitation of the women around him is the inverse of Travis’ happy-go-lucky savior, and Smith is obviously relishing his chance to possibly create an iconic villain in a burgeoning film series.

The climactic throw-down between Travis and Terry is a savage highlight in a movie otherwise devoid of straight up action set pieces. Both Taylor and Smith bring the full force of their respectively impressive physiques, tossing one another against walls and generally appearing as if they want to squeeze the life out of the other. It’s an incredible feat of raw choreography, more in line with pro wrestling and capturing the bare knuckle energy of the brawls MacDonald deftly described in his books; short bursts of workmanlike prose that made the reader feel every single blow and breaking bone.

Scoring it all are the erratically jazzy tones of composer John Carl Parker. A TV veteran, dreaming up themes for everything from Gunsmoke to Dallas, Parker’s mix of heavy brass and percussion keep Darker Than Amber feeling oddly laid back, considering the dire mystery at hand. Because at the heart of these stories are extended hangs, and Clouse often seems content to let the audience simply become a spectator in Travis’ living room, listening to the next record and processing whatever clues this unlicensed detective has uncovered while snooping about quaint shops and cruise ships.

Sadly, Darker Than Amber didn’t really land with audiences, finding regular rotation on television before vanishing almost entirely on home video (the movie never made the jump beyond VHS tapes, most of which strangely edited the brutal final fight). There were rumors of a resurrection for the character not long ago, with James Mangold behind the camera and everyone from Christian Bale, to Matthew McConaughey and Leonardo DiCaprio rumored to be captaining The Busted Flush.

In the streaming era - where Amazon and Netflix often greenlight auteurist driven works of long-form storytelling (or even solidly constructed middlebrow fluff like Bosch) - the biggest McGee mystery is why these novels continue to sit on the shelf, gathering more and more dust as the years go by. Their often sub-200 page structure would be perfect for the format, providing self-contained adventures that’d allow an entirely new generation of viewers to become casual acquaintances during Travis' never-ending retirement. The world is ready for his return, as we could use a bit of John MacDonald's old school musings, while we try to escape a real world gone mad.

*In fairness, there was a TV Movie starring Sam Elliott (titled simply Travis McGee) from 1983 that's worth seeking out.

**A trend established in The Deep Blue Goodby with Junior Allen, who killed the one woman we get the feeling Travis could’ve possibly loved for his whole life, wounding our already damaged hero for the rest of the series.

Jacob Knight is the Editor-In-Chief, co-host, and co-founder of Secret Handshake.

Comments